Portland, Oregon (United States)

ERION MOORE

Scleroderma Stories Issue 3

Please introduce yourself

I’m from California (the Bay Area), but I live in Portland, Oregon. I have a service dog named Coco, and I have been diagnosed with scleroderma since 2008. It affects my joints, so I have a lot of mobility and range of motion issues. But I’m still pretty active because I do adaptive sports. I like watching sports and comedy. I enjoy boxing, basketball, and football – both pro and college.

What adaptive sports do you do?

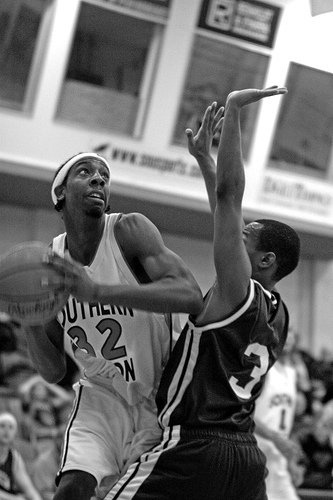

I actually played college basketball and did some track. Then, scleroderma took that away because you need to have control of your whole body to play sports, or at least to play the able-bodied sports. I was no longer able to play those, but I did switch over to adaptive ski. It’s hard because when it’s a sport, you grow up and play it. You love it. You’re good at it. You want to be able to play all the time.

But luckily, I was able to find a hobby, a sport still, such as skiing and table tennis to fulfill that void and still get a sense of activity, recreation, and such. I think I was trying to fill that void and find another physical activity to replace it. It’d be like if you were a pianist, and then you were able to do another instrument. It may not be the same, but you’re still able to make noise.

And I do some movement activities – sometimes yoga or boxing, actually. I don’t actually fight, but I do punching just to keep my body moving. I think there are around 26 paralympic sports, and I’ve probably tried all of them. Or at least 25. I had to do something. I was losing my mind not working or going to school. There was a point where I did water aerobics three times a week. In addition to boxing, I did lameca (Filipino stick fighting) one day of the week. Then I do pilates and yoga. That was my life for a while.

I think water aerobics is probably the most effective of everything I did. There’s resistance, but not too much. It can hold you up. So water aerobics was definitely key. I recommend water aerobics to a lot of people, especially as you need to get out or you gotta get your body going.

When were you diagnosed with scleroderma?

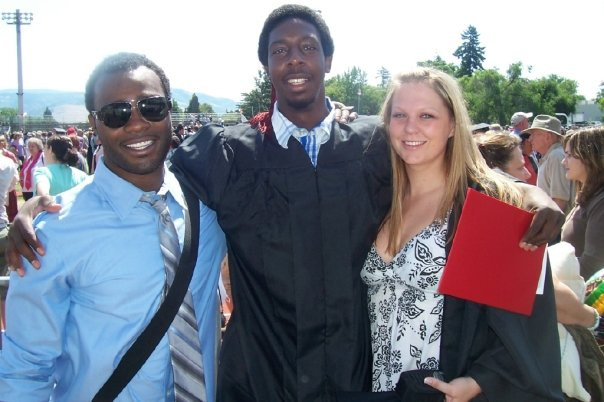

I was 25. Well, I had it two years prior, which was my last year in college, but it didn’t get diagnosed. I was having mobility issues, and then over the next two years with different doctors, we started trying to figure out what was going on. Then, a couple of months after I turned 25, finally we got it right.

The very first symptom I had was acid reflux from GERD, but I didn’t pay attention to it because I was just eating a lot of food. I was still thin: 6’6” and about 200 lbs, so I wasn’t big. I tried to eat a lot of food to gain weight. So, when I had acid reflux, the reaction was just, “Oh, cut back on your food.”

I also had Raynaud’s. I had problems reaching in the freezer. It got real bad, to where I didn’t even want to go in the freezer. And at least for me, when you don’t know why you can’t reach into the freezer, I was thinking, “Well, it’s got to be me. What’s wrong with me?” I just dealt with that issue, but what actually really got me to the doctor’s was basketball. I still played basketball at the time, but I had problems shooting. I was telling my doctor that something was wrong. I was like, “I can’t shoot the ball the same… I don’t have the endurance…”

I started taking pilates and all these other exercise classes, like yoga. Anything you could think of that’s full body and mind, I was taking it. It wasn’t working, so I finally decided, “Okay, this is beyond me now.” I went into the doctor’s one day and said, “Something’s absolutely wrong, and we’ve got to figure this out.” It was right when I said, “Look, my shoulders are tight,” that she put all of the appointments that I’d been going to together and said, “Okay, I think this is what it is.”

She brought in her colleague, and they started doing that test where they grab your skin on different parts of your body. Eventually, she decided, “Yeah, this is it.”

How did you react to the diagnosis?

I actually didn’t take it as serious as I should have, and that’s most likely because I hadn’t heard of scleroderma. The ironic part of why it wouldn’t even make sense that I didn’t take it seriously is that the head rheumatologist came in. They talked, and he told me I wouldn’t play basketball or work probation anymore (I was working juvenile probation at the time). He said, “I suggest you get health insurance because your life is about to change.”

I kind of just looked at them. I took them seriously, but not too seriously. I had never heard of scleroderma, so I just thought “all right, okay.” He begged me for months to get concerned, but I still was busier paying off student loans.

Why do you think you didn’t take the diagnosis seriously?

There was nothing other than tightness in my shoulder that made me think anything was going to get worse. So, I didn’t really follow up for a couple months. I just thought, “Ah, I’ll get over it.” He didn’t show me pictures, and I couldn’t find stuff online at the time.

When it comes to rare diseases or anything that isn’t a common conversation, information just wasn’t available on the internet back then. You would find stuff, but you’d have to dig more into research. Now, I obviously can type in the words and get everything. But at the time, it was just the Scleroderma Foundation and the average demographics, where they’d say older Caucasian women. I really wasn’t worried about it. I didn’t see anything that made me think I would fit in so quickly.

It’s a lot to take in. I had that fighter mentality, as an athlete, that helped. There were a lot of reasons why I didn’t take it as seriously. I think it was more because I had never heard of it, and he didn’t say I was going to die. If he would have mentioned something like “You’re going to lose an arm” or “Your heart’s going to fail,” I think I would have. But he never said what was going to happen. It just sounded like he was taking the two things that I’d done a lot, which was work and play basketball, and just saying that I won’t be able to do those.

At the time, I was thinking, well maybe it’s because my shoulders would be hurting or tight. I didn’t know they would do what they have done; it became where I couldn’t even use them much. I just thought, “Maybe I’ll have problems doing it, but that won’t mean I won’t have a basic, normal life, quote unquote.”

Was there a specific moment when you realized the seriousness?

The day I took it seriously was the day the head rheumatologist called me and said, “I’m going to give you my house number. You tell me when you get health concerns.” That’s exactly when I knew.

A doctor doesn’t just give you his phone number. I wasn’t even his patient; he was the head rheumatologist. Maybe he figured I needed some trigger words. He said, “I’m going to give you my house number. You have to call me.” I realized that there was something beyond what I was thinking of. That’s when I really said I’ve got to get help. Within about a week or two, I went to a library to research scleroderma, called the Scleroderma Foundation, went to a support group…

I wish I remembered his name. I would love to call him and say, “Man, you were so right.” But, unfortunately, I forgot his name.

How did you feel in the time shortly before and after your diagnosis?

That last year was tough because I didn’t know what was going on. My doctor had originally said it was rheumatoid arthritis. She just said, “you can’t really do much, but I’m going to give you medication, so just work around it.”

If that’s all you think is what’s going on, you just think, “Man, this thing is tearing me up.” But then, just having the doctor that stayed on me about getting insurance and taking care of myself and then, really, the medical team helped me. It’s important to have a medical team that you work well with. It’s important to have doctors who actually listen to you if you want to talk.

What is your relationship with your medical team like?

My doctors recommend procedures and medication, but they also know I’m not going to do it just because they said to. A lot of times with my rheumatologist, when we meet, she knows I’m coming with some research. She has hers, and we’ll discuss it. We’ll flip back and forth.

We’ll discuss if it’s a great option and what the risks are. We know the pros are supposed to be good, but we talk more about the risks. She knows that, yes, I want my shoulders better, but I’m not going to do some random surgery that could possibly go wrong. I would always say that the medical team and a large support team is important.

How did your condition develop after your diagnosis?

From 2008 to about 2011, my mobility started to slow down. I was starting to get the internal issues, like the scarring.

I had real bad acid reflux, to the point where I haven’t laid flat to sleep probably since 2009. It was that bad, even with medication. I also had stomach ulcers. That was probably one of the hardest things because I confused it with the acid reflux, but it actually burns holes in your body. That probably made me lose the most weight. I dropped 30 lbs in a couple of months. 6’6”, 200 lbs is already skinny, but to lose that 30 was real bad. I was also anemic.

I had finished college in Oregon, gone back home and gotten diagnosed in the Bay Area, then moved back to Oregon because of my work and health. Again, the doctor in Oregon was telling me it was more serious than I was taking it. She said, “Look, you gotta take care of these issues.” She did the same thing. She called me one day. The first time, she said she needed me to take the day off and go get some labs or something.

I didn’t listen to her, but at that time, I was starting to faint just walking maybe 15 or 20 feet. I started having that issue in the shower, where I wouldn’t last in the shower long. I got a chair just because I couldn’t stand up.

She called me later that day while I was on my way to work and said, “We got you a bed at the ER.” I just said, “ER??” I never even knew they could order a room for you at the ER. She told me I was at risk for a heart attack. My reaction was, “Well, let me go to my job and tell him this is what’s going on.” But she told me, “I don’t even think you should be driving. You need to pull over and call an ambulance.” Those were the first couple of issues.

Then all of a sudden in 2011 and 2012, I started getting very physical issues.

My fingers contracted, and so did my knees, my hips… all of my joints except my feet. My feet stayed fine, but my skin was so tight. You could see it pull from my thigh up to my chest. I couldn’t open my mouth maybe more than four popsicle sticks. My elbows contracted. My shoulders subluxed – which means partially dislocated, so it was like still on the joint, but kind of off. It happened to both shoulders; anything that happened to one side happened to the other. Anything that contracted on my left side did on my right as well. My fingers are all contracted, but my thumb and pinkies are dislocated on both hands. My elbows do not straighten either. They go probably a little past 90 degrees. I also lost more weight. In March 2012, I remember getting stuck on the bed and thinking I couldn’t get off. I thought I would have to jump off or roll off. That was probably when it was at its very worst. I could barely move.

In January, I could reach on top of the freezer, even though it was a struggle. By March, I even couldn’t reach inside of the refrigerator. At that point, I was starting to load up the sides of the doors or not put anything in the fridge.

How did you adjust to the changes in your mobility?

Back then, I didn’t know about the adaptive stuff that I’ve put all over my apartment recently. At that time, navigating yourself and without the internet, you don’t know all of this. Some of this information probably existed online, but who’s telling you, right?

A lot of the physical or occupational therapists didn’t say anything. They didn’t ask, “How are you getting in your refrigerator?” Occupational therapists do think about activities of daily living, but at the time, I didn’t know I could get home occupational therapy. Even though I was able to get out of the house, I really wasn’t safe outside of the house.

And I didn’t know that somebody should have said, “Hey, what’s it like living in your apartment by yourself? Are you able to do these things?” No one really mentioned it. I just started doing stuff alone. It was pretty tough, but I was learning everything because I’m just someone that’s going to figure it out.

What was the hardest symptom?

The contraction. My joints, my hands starting to curl up. If you open your hand right now and close it, you can do everything you want with your hands. Now, just ball it up like you’re holding a microphone. That’s what my hands are stuck at. And now try to do the same thing you would want to do, like scratching your eye, digging your nose, whatever you have to do. This is what your hand is.

Sometimes I would tell people – honestly not mad at them – but I’d tell them, “Hey, you want to try what it’s like to live with my hands? Let’s do this.” And we’ll try something, and I’ll see how long they can last.

I would say, of all the joints, it’s my shoulders. I want to be able to reach out or reach back, but I can’t. I can be creative without using hands, and I can be creative without straightening my elbow. I’ve got long arms, anyways, being 6’6″. Not being able to use the shoulders is probably more crucial than any other joint that I need. And you’re talking to someone that’s athletic, someone that lived alone, a germaphobe. I like things cleaned a certain way. I like all that stuff, but I can barely do it.

Have you gotten more used to your lack of mobility over time?

I don’t think I’ll ever get used to it. There is no replacement. But I won’t tell other patients, just to make them feel better. Seriously, it’s hard for a lot of people.

When I went to a hand surgeon in New York, he was only doing fusion, which basically means he would fuse your fingers into a certain position. If you straighten the index and bend it at the big knuckle just barely, that’s the finger. That’s the position your fingers would be locked in. It’s probably better for some people. But me, I’m just always thinking, well maybe in five years some doctor will come out with some surgery that doesn’t require a permanent fix.

When the doctor looks at the surgery, he always asks you that silly question, “Why do you want to do it?” I couldn’t believe he asked. I knew it was a part of his job, but I just said, “Come on, doc. I need my hands. These hands are waiting for love and knocking people out.” I was joking, but he loved it. Then I explained, in all seriousness, that I need these hands. I’m a person that uses my hands for everything. I want to play sports. I clean a lot – or used to – and now I can’t do it. I started having to get caregivers. I don’t want to rely on people. I like living alone.

I mean, of course everybody wants their hands, but if you’re a bodybuilder, you may not need your hands. There’s different exercises you can do to still get that strength. Maybe, I don’t know. This was all before I got a stem cell transplant.

Could you share more about your stem cell transplant experience?

I found out about the transplant around 2010, but I didn’t have the right insurance to cover it. I had to wait until I got social security. I waited 2 years. By the time I got there, I was probably down to 125 lbs. I could barely move, couldn’t look up, couldn’t look to my left or right, couldn’t open my mouth, couldn’t open my fingers. I got accepted that summer.

In October, I went out and started doing the outpatient, where you get your labs and do overnight chemo. All of that was actually pretty fun. It was in Chicago. It was cold, but the staff was great.

I had different people come visit me in Chicago. Some flew. My grandmother took a three-day train because she’s scared of flying. I told her I wouldn’t have taken a three-day train anywhere, but that’s grandma. She came up, we had fun, and then she stayed with me until the day I had to go into the hospital.

I did chemo for about a week. It was six days. On the seventh day, which was a Tuesday morning, they put back my stem cells. Two days later, Thanksgiving 2012, I was able to move my wrist. The skin had started to loosen. I also have vitiligo, so I was starting to have white spots all over my body. That went away too. Now, people don’t even know I have vitiligo.

I would say the stem cell transplant was the biggest change in my life. I was skin and bones, and I needed a lot more help. Over time, I started doing water aerobics, yoga, boxing, lameco, skiing… I’ve tried every sport that you can think of. I think that’s what helped me gain mobility.

Sometimes, I can travel with the walker instead of the scooter. The transplant stopped the progression of the disease. But, by that point, whatever damages you have, you’ve got to deal with. Some of my internals got a lot better, but if I would have had the transplant prior, then maybe my joints wouldn’t be in the condition they are in today. That’s life.

How did scleroderma impact your ability to work?

I stopped working for a while because of it. I liked working in probation. I liked working with offenders. It could have been partially my size for a while, but I didn’t really have to deal with the physical part of it. I never had to tackle anybody. Sometimes, size is an advantage, where people think twice about that. But with my hands, elbows, hips, and back the way they are, I’m just the target. I can’t stop any of that, if it happens.

Scleroderma takes away some of the jobs you may want to do, depending on what work you enjoy. I’ve also done other labor-type of work that I enjoyed. Now, I wish in the years from 2010 to today, I had focused on learning computers. They’ve got all kinds of speaking apps, and I can actually type pretty well. I just didn’t learn Microsoft in that whole time. I never learned Office or anything.

Did scleroderma affect your confidence?

It’s not that bad. Before the transplant, I was just staying at home, so there was nothing to worry about. After the transplant, I thought I would do some old Benjamin Button type of thing, where things reverse, and I exercise and start looking like the old me. But, I’ve accepted that part – that I’m not going to be that same person.

So the confidence isn’t too bad. I think a lot of it is that I’m a strong advocate for myself. Also, a lot of my friends and the people I met before the disease stayed with me. So that’s key, right? It’s good to have the same people that are with you through this journey.

When I moved back to Oregon, I didn’t see people for years. I didn’t travel much. Some people had not seen how bad it affected me. They didn’t know I ended up in the scooter or wheelchair, or that I dropped down to 130 lbs, or that I could barely move. Some of them didn’t know because over the phone, or even if you did see me in person, I didn’t act differently. I wouldn’t talk about how bad things were going. It wasn’t like I was hiding it. It was just that if I was able to do the daily living, if I was still able to do most days, then there was nothing to talk about, in my opinion.

So I would say it didn’t take my confidence too much. I’m probably still just as bad as I was before the disease.

Did you have a lot of support from the people around you?

Yeah, definitely from family and friends for a long time.

I would say coworkers are different. I don’t want to put someone on blast if they happen to read this, but there were people that didn’t believe there was something wrong. Then they saw me later and were super apologetic. They were like “Oh man, I didn’t know that it’s as bad as you said it was” or “I just couldn’t tell” and so forth.

But luckily, the family and most of the close friends thought, “I know this guy. He wouldn’t want to lose weight. He doesn’t want to not hang out.” They definitely were part of keeping me confident and feeling “normal”. If you talk to them, I was more of their console than mine. They were usually calling me, feeling bad because, as they would tell you, I never complained.

As a matter of fact, at one point, nine of my ten fingers had split to the bone at the knuckle. You could see the bone cap, and I still never talked about it. I never not told anybody. If you asked me, “What’s the body looking like?” I would tell you right from the beginning. But I wouldn’t just bring it up and make it a conversation for no reason.

This was the kind of stuff I was dealing with. But when they’d call me, I’d say, “Oh, I’ve been good, what’s going on?” And I meant it. Everything was good. Things were reciprocated. If I talked to them and worked with them to do their thing, then if I needed that, they would return that favor. That’s how I felt. We kept it going and stayed strong.

I wasn’t a depressing conversation. And I don’t mean that in disrespect. But they didn’t call and worry that it was not going to be a good, fun, or normal conversation. That’s some of the things they liked. We would still laugh, get mad, talk, whatever we normally did. Nothing verbally changed. Things stayed constant. Things were the same. Consistent. And I liked that better. I didn’t bring them down. Everything pretty much remained the same with friends and family. I may not travel as much, but we still talk as much, we still guide, or I still support.

How has the pandemic impacted your life?

It definitely changed things. I don’t have a vehicle yet, and I rely on paratransit, which is for the disabled. Depending on the county or state, sometimes you don’t get a ride because they say, “No, we’re only doing medical appointments.” That becomes difficult if you want to go somewhere other than the doctor’s.

Then socializing, obviously. You have to worry, “Who was that person hanging out with?” Even if I stayed home and stayed to myself, I have health home care workers that come a couple of times a week. I don’t know what they’re doing outside of here. Some of them take corona very seriously, others say they never put themselves at risk, but they’re also not not trying to. That becomes a concern because I can’t control what people do away from me. Some people, if they believe they won’t get it or they can live through it, then they’re going to be around people that probably shouldn’t have that.

If I go to a friend’s house, I’m definitely in the backyard with the mask on, and we social distance. We literally social distance. If we order pizza, I get my separate box, and they drop it off at this spot. We’ve figured out how to keep our distance from each other and just sit with our mask on in the backyard or at the patio area, keeping the distance. It’s still a low-risk, but there’s still the social aspect.

I usually travel in the summer to visit family and do some cycling. I wasn’t able to do either one of those. And skiing, too. I like winter activities. I don’t think the sport itself would be difficult, but in certain places, the hospitals are filled up. If I get hurt, I’ve got to be worried about if there will be a lot of COVID patients at the hospital and if they have room.

Then travel, too. If I’ve got to fly to a different state, how safe is flying right now? So I would say it takes away some of that activity that I really like to do, such as visiting family or friends and then skiing in the winter. Those are the biggest barriers or obstacles that have been happening because of COVID.

What are your goals or dreams?

I want to continue to be physically active. Like a lot of other patients who have the physical limitations, there’s no prognosis on whether you’ll get better or stay at your current condition.

My stem cell transplant stopped the disease’s progression, and I’ve made some improvements – not necessarily all the way, but until there’s a definite no, I’m just going to keep on trying. I see my doctor around once a year, and each time I’ll tell her, “What have we found on muscle? Tissue? Ligaments?” I’m looking across the world for something.

I also want to get better at skiing. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to go on runs on myself, but I want to be able to just do some runs without worrying about getting hurt. I would say definitely my number one goal is to try to gain more mobility and to stay active while doing it.

Another goal is to just serve the community. I still want to work in the criminal justice field, whichever way I can get around. I like working with justice-involved individuals.

What helps you stay motivated?

It’s hard to be optimistic for different reasons for different people, but that’s what keeps me motivated. Like I said, my friends talk to me, and I hear that, “Man, I would never have been able to be in your situation,” or “I come to you for problems when you should be coming to me,” or “Erion, I’m watching you go through this.”

So that’s the motivation, right? If I could do anything for somebody, that’s to be support. I’m not wealthy, I don’t cook as much, so I can’t do other things that I probably used to do when someone needed help. But talking is “Oh, I could do this.” I’ve got to stay positive for that.

I think long and wide, as I call it. I’m thinking long term, and I’m thinking multiple outcomes in the meantime. I want to be able to walk upright without assistance. That’s my long-term goal. Then wide is “Do I keep going to rehab?” “Do I walk around my apartment upright?” All of the things to get to that point. That’s why I stay active. Because walking unassisted is one of my goals. We don’t know if I’ll ever get to it, but as long as there’s a gray area for me, I will try to get to it.

It’s hard to stay active. Sometimes, you just want to sit there, and you think “You know what? I don’t feel like doing this.” I’ll put challenges on myself, where usually someone else makes me do it. That’s why it’s one of my goals. When you’re not active, and then you do it, you feel the difference. When you feel at the place you want to be, you feel active, and you feel like you can do more things that you want to do. When you feel good about yourself – your physical self – then you start doing more things. Or you try to, at least.

Could you please talk about your experience with support groups?

I am in some scleroderma support groups, and I’m also in the local one, which is now all virtual. I would say by the time I actually started using those and Facebook, I was already at the point where I knew what I needed to do or I was already doing it.

But, it was always good to talk with other people who are dealing with the condition. Obviously you’re connected with other people who are going through the same issues, right? You can say, this is the kind of thing I’m dealing with, and they’re like, yes, me too. And they’ll share how they navigate. It was good to network with other people and discuss things you’d like to change or things you need to know more information on.

I also felt good helping people who were newly diagnosed or who had figured out how to get something done. For instance, wound care. It was good to talk to other patients about things I did or what they did and try different methods.

Like I mentioned, I went to my first support group in San Francisco after my doctor gave me his number. It was all older women. I didn’t have a problem with it, actually. I definitely enjoyed my time, which is why I kept going. We’re getting different perspectives and different conversations.

When I moved to Oregon, it was a little more mixed, with younger and older. I think maybe one other guy came. There weren’t really a lot of men that were coming. Now, because of the pandemic, we’re virtual up here in Oregon. And I went to the national conference. That was big because I was seeing four or five hundred people all dealing with the same condition.

Did you enjoy the national conference?

Yeah, it was good. You started seeing more men, you started seeing younger people, African-Americans. Whatever you didn’t see before, that you didn’t even know was around, now it’s everywhere.

There were so many workshops. Obviously, you still do your own research, but now there were actually workshops on social security, self care, loans, and everything else related to scleroderma. There was even one for the caregivers, whether it’s partners or actual caregivers. They just had workshops for like three days, so that was fun.

It rotates across the country every year. I think my first one was in Boston. I got to go to Boston, hang with other patients, and learn more that way, so it was really cool. Whenever I take a trip, whether for work or family, I’m doing something else in that city. It’s great to just see them, but I’m also going to explore.

Do you enjoy travel?

I do. And I regret not traveling when I was healthy. I really was a workaholic. Anytime I had an extra day, I was like, “Hey, you want to work another day? I’m doing it.” I didn’t realize how much I’d like travel because I hadn’t traveled much before college, other than for sports.

Now when I travel, I’m in a scooter or I use a walker. I have to have assistance. I have to find the right hotel… I would’ve loved to have been my old self, 6’6″ and walking down Italy or Austria above the crowd. I can see over everybody and know what I’m doing, versus in a scooter, it’s always, “excuse me!” It would have been different then. I’m enjoying traveling now, but I’m ready to expand. I hope I can travel more in the future. I didn’t do it when I could have. Now, I tell people to just travel that first time you can after college. It makes you think different, rather than saying, “Oh, I’ll wait after this.” No, do what you can while you’re young.

I understand that it’s one of those things where you don’t want to mess up your timing, your flow, if you’ve got a routine. But, I was the kind of person where, if I had to go to Utah for one conference for one day, I would get so much done in that day. I’d be at the conference from eight to five, and from five to eleven, I’m doing something outside.

Some people don’t want to squeeze a trip in a couple hours. Some people can’t hang out that long. But, if you can fly away for a weekend, if you get off Thursday at four or get done with your class and you feel like you don’t have to study too hard, you can catch that 5:30 flight and come back Sunday. I feel like that’s still enough time.

Is there anything else you wish you had done before your diagnosis?

I was a grandma’s boy to the fullest. If she told me to jump, I’d say, “how high?”

She told me right before she died, and this was after scleroderma got to me, “I wish I would’ve seen you walk again.” I was doing the rehab, and I was getting better. She said, “I just want to see you walk and get ready to have kids.”

She never told me that when I was in college or when she met any of my girlfriends. She did not tell me because she knew I would do it for her. If she said, “Hey, Erion, I want you to have a kid,” I would have done it that weekend just because she told me. It would have been someone I liked; it wouldn’t have been some random lady on the street.

But I wish she would’ve told me everything she wanted. She always worried that would put pressure or that I would drop everything for her. That was probably the thing that she told me that I wish either she hadn’t told me that day or she would’ve told me earlier.

She and I were talking as she was dying, and when she said that, I was like, “Now why would you do that?” That’s all life. We were having so much fun. She knew it was time to go because the cancer was too bad, and she was starting to lose it. I know she would not want me to still think about that day, but obviously you will, if that’s the last words you hear.

For scleroderma, I wish I would have known more about ligaments and tendons and how the muscles work. There’s a lot of body damage that we can control. There were some things in rehab that I learned later, or that I didn’t know at all, that could have made the condition less worse. I didn’t know how to prevent it. I didn’t know what other things I could do. Then, there are also new devices. There are newer things.

For instance, the arm. I could have been wearing braces for a long time. I have the pain tolerance for it, but I didn’t know. Even if I hadn’t gotten this disease, when you get injured, if you have a stroke, or if you break something, you have to learn how your body’s going to reheal itself.

I say that because that probably would have been maybe more important than what my grandma said, just how the physical part of the body works.

What advice do you have for people with scleroderma or other chronic illnesses?

My best advice would be to stay physically active (even if it’s lifting your arms while seated or laying down, be as positive as possible, and advocate for yourself as a patient!

Be sure to follow us on Instagram and Facebook (@sclerounited) to see more scleroderma warriors’ journeys in our weekly Sclero Sunday series.

Are you a scleroderma warrior? We’d love to interview you for Scleroderma Stories! Please visit tinyurl.com/share-my-sclero-story or email us at contact@sclerounited.us